Ikiru (1952)

Kanji Watanabe is a middle-aged man who has worked in the same monotonous bureaucratic position for decades. Learning he has cancer, he starts to look for the meaning of his life.

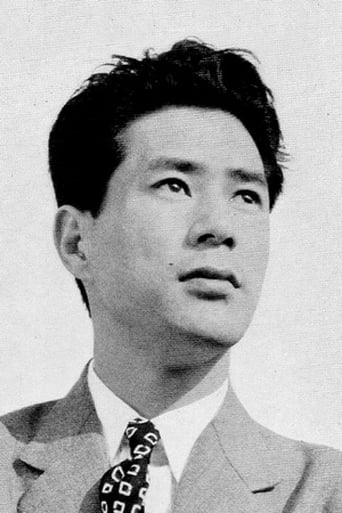

- Akira Kurosawa

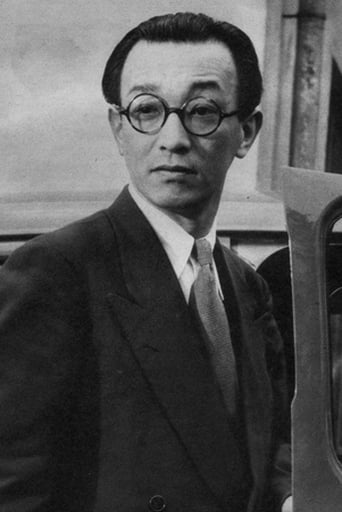

- Shinobu Hashimoto

- Akira Kurosawa

- Hideo Oguni

Rating: 8.308/10 by 1173 users

Alternative Title:

Ikiru - DE

Viver - BR

Vivir - ES

Ikiru Einmal richtig leben - DE

生きる - JP

Ikiru - US

留芳颂 - CN

活下去 - CN

이키루 - KR

살다 - KR

Doomed - JP

Viver - Ikiru - PT

To Live - US

איקירו - IL

Vivre - FR

Ikiru: Einmal wirklich leben - DE

Իկիրու - AM

Country:

Japan

Language:

日本語

Runtime: 02 hour 23 minutes

Budget: $0

Revenue: $55,240

Plot Keyword: dying and death, japan, bureaucracy, age difference, praise, office, night life, sense of life, playground, obsequies, swing, loneliness, office politics, infatuation, wake, public works, bureaucrat, thoughts of retirement, terminal cancer, city park, civil servant, monotonous life, accomplishments, office gossip

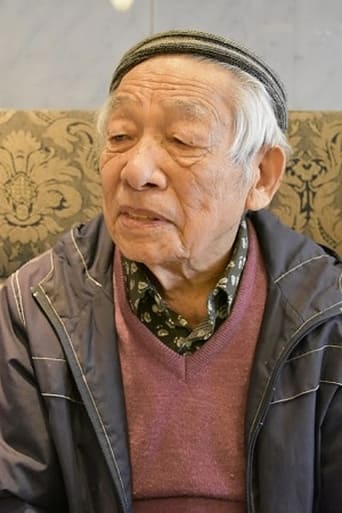

Takashi Shimura is "Watanabe", an elderly civil service lifer who is told that he has terminal stomach cancer. After years of a disciplined, rather pedestrian existence he now feels a need to emancipate himself and start to live a little. The story is told through two threads: one looks at the end of the old gent's life from his own perspective; the second takes a retrospective view from the wake as his family and colleagues gather to remember him. Kurusawa is clearly making a point with this delicate, poignant film - perhaps life needs to be appreciated and enjoyed - not necessarily in a jovial, happy fashion, but by achievement. In this case "Watanabe" sets about using his position to help locals get a park, but he also starts an empowering relationship (platonic) with a younger girl, who is quite keen on her food, it has to be said. As his colleagues at the wake suffer from excesses of saké their traditionally stiff, reserved, view of their late friend becomes more of a tool to evaluate their own roles and purpose as they determine to be more like him.... The writing has plenty of humour and again, Kurosawa uses weather as a wonderfully potent instrument to create a great atmospheric feel to this gentle story of profound change, and - maybe - contentment.

I watched the English follow-up version (Living) before watching this original, and wished I had reversed my order. I liked Living much more than this original, but since both were written by the same Japanese scriptwriter, my preference might be cultural rather than due to quality issues, not to mention the scriptwriter had come up with improvements through the intervening years. The club and bar scenes near the beginning seem to go on much longer than in the remake, or at least it felt like it! And the same for the later scenes with the young woman. Then again, that wouldn’t be surprising since this older version is 40 minutes longer. Still, the differences in the details based on the separate cultures are interesting to note, and I recommend both versions, though I would start with the older one as I mentioned above.

Typical Kurasawa creative framing in the beginning of the movie. The scene of dancers shot through bead curtains swinging in time to the music was brilliant. His choice of Miki Odagiri for muse is brilliant. Her laugh is infectious. The last act stuck me as rather static. It's perhaps from cultural mores about the dead I don't understand (like the taboo of not ever sticking your chopsticks into the rice bowl!). Kurasawa waxes philosophical on life and government here, and indeed, nothing has changed in 70 years.