Against the Rest of the World / Peasant Masses

In the 19th century, Europe's farmers were finally free. But the Industrial Revolution and modernization precipitated their decline. Deserting the countryside, they left en masse for the cities. As the rural exodus gathered momentum, conservatives saw peasants as the embodiment of all traditional values. Reputed to be more obedient and hard-working than workers, they were the main cannon fodder of the First World War. Fascism and Nazism took this mystification to the extreme, invoking the eternal peasant as the guardian of soil and blood. But the real peasant is subject to the dictates of the state, technocrats and agronomists. Unaffected by political regimes, the steamroller of industrial agriculture has continued to advance ever since. Yet the peasants are still there, making other voices heard.

- Stan Neumann

Country: FR

Language: En | Fr | Ga | It | Es

Runtime: 56

Season 1:

By the 6th century, the disintegration of the Roman Empire was complete: no more state, no more big cities. The European peasantry was born. A change of scale. The great Roman commercial agriculture disappeared. These first peasants, freed from the weight of the State, taxes and the obligation to feed the Empire's major cities, produced only as much as they needed. Peasant communities were freer than ever. This golden age came to an end in the 8th century. The new warrior elites imposed a return to domination, taxes, and the invention of drudgery and serfdom. The Church took part in the reconquest, tracking down the old rural cults.

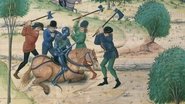

Around the year 1000, growth resumed in Europe. This was the product of the work of peasants, who were even more exploited and despised, especially by city dwellers who were making a comeback. The rise of commercial agriculture was based on cereals, the main source of profit for the ruling classes. The banks of the River Po and the coasts of the North Sea were drained to conquer new wheat lands. The destruction of these wetlands disrupted the peasant economy and led to catastrophic flooding, the effects of which are still felt today. In the 14th century, famine, war and plague put an end to growth. The era of the great anti-feudal revolts began, with their mystical and egalitarian overtones. From the French Jacquerie of 1358 to the German Peasants' War of 1525, all were drowned in blood.

Peasants don't need to know. If they knew how to read or write, they could challenge the titles of the rulers and the authority of the Church, like the Italian miller Menocchio, declared a heretic and burned alive in 1600. Peasant knowledge was just as suspect. Peasant witches, often simple bonesetters, were hunted down, accused of worshipping Satan and burned by the thousands. On the threshold of modern times, in the name of progress and profitability, the dominant classes launched an offensive against the old village solidarities. England set the example by privatizing communal lands. By depriving farmers of an indispensable resource, they were condemned to disappear. France followed a different path. Still in the majority, its peasantry played a major and little-known role in the Revolution which, in 1789, put an end to a thousand years of feudal rule.

In the 19th century, Europe's farmers were finally free. But the Industrial Revolution and modernization precipitated their decline. Deserting the countryside, they left en masse for the cities. As the rural exodus gathered momentum, conservatives saw peasants as the embodiment of all traditional values. Reputed to be more obedient and hard-working than workers, they were the main cannon fodder of the First World War. Fascism and Nazism took this mystification to the extreme, invoking the eternal peasant as the guardian of soil and blood. But the real peasant is subject to the dictates of the state, technocrats and agronomists. Unaffected by political regimes, the steamroller of industrial agriculture has continued to advance ever since. Yet the peasants are still there, making other voices heard.