The Professional Politician

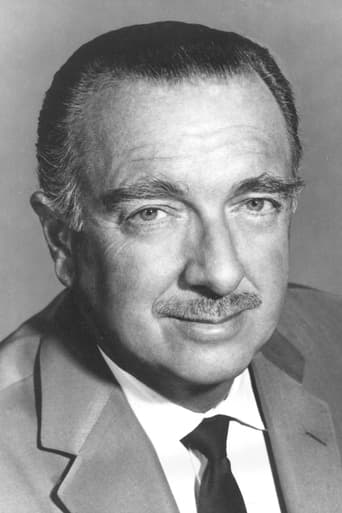

In our nation’s early years, taking part in political affairs was considered a duty and an honor, but not a way of life. It was not long, however, before the professional politicians, and the parties they represented, began to find their way to the White House (Martin Van Buren, James Buchanan, Abraham Lincoln, Lyndon B. Johnson). While the skills necessary for political success can be helpful to a president, they are not sufficient to guarantee success in the office.

Country: US

Language: En

Runtime: 53

Season 1:

The last thing that the Founding Fathers envisioned was a hereditary chief executive. After all, they had fought a war in part to rid themselves of a king. Yet power inevitably passes from generation to generation, and several families have returned to the White House as though born to it. The stories of these four men profiled in this episode (John Quincy Adams, Benjamin Harrison, Franklin D. Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy) reveal both the blessings and the curses of inherited power. Two of them were ill-at-ease with their lofty legacies and struggled as president, while the remaining two flourished in the exercise of power.

Nearly one in six American presidents has died in office. The vice presidents who succeeded them were often chosen because they provided some electoral advantage (John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Andrew Johnson, Chester Arthur, Harry Truman). What happens when such a man takes office – frequently facing widespread conviction that he is unworthy of the powers he inherits?

Is an independent cast of mind the best approach to the presidency? The four men profiled in this hour (John Adams, Zachary Taylor, Rutherford B. Hayes and Jimmy Carter) pursued a course that took little account of political affiliation, becoming presidents, in essence, without being politicians. Taken together, they present a cautionary tale: all had difficult presidencies, and neither of the two who sought a second term was granted one.

In our nation’s early years, taking part in political affairs was considered a duty and an honor, but not a way of life. It was not long, however, before the professional politicians, and the parties they represented, began to find their way to the White House (Martin Van Buren, James Buchanan, Abraham Lincoln, Lyndon B. Johnson). While the skills necessary for political success can be helpful to a president, they are not sufficient to guarantee success in the office.

It is often observed that American national identity is less a condition than an idea. What we have come to refer to as “the vision thing” is an expectation that our presidents will bring to the office a particularly strong sense of national mission. The four chronicled here (Thomas Jefferson, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, Ronald Reagan) may have understood the special character of America in different ways, but in all cases a belief that there was a distinctly American way of doing things guided their decisions.

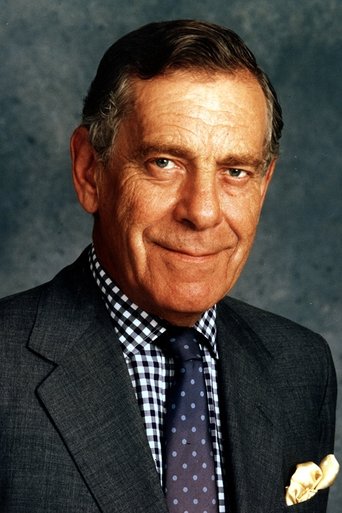

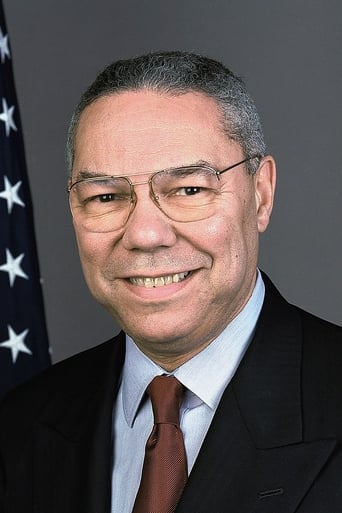

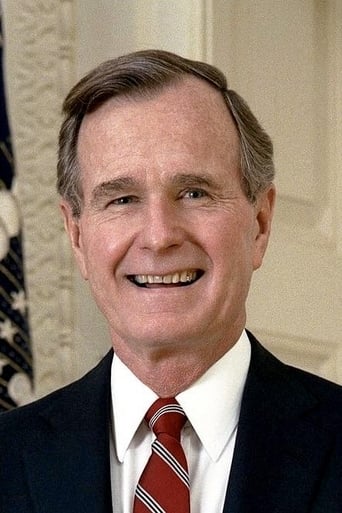

The president has no greater responsibility than representing the nation on the world stage. These four men (James Monroe; William McKinley; Woodrow Wilson; George H.W. Bush) engaged in this task at critical times in our national history and their achievements on the world stage stand as their most durable legacy.

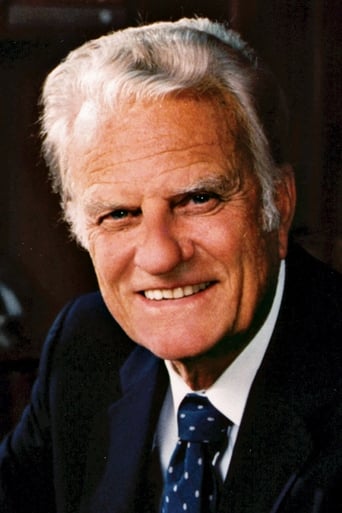

From the beginning, the presidential office has beckoned to national heroes renowned for their selfless service to their country (George Washington, William Henry Harrison, Ulysses S. Grant, Dwight Eisenhower). This affinity is especially strong for men of military fame, for the president is formally commander-in-chief as well as symbolically the steward to the national interest.

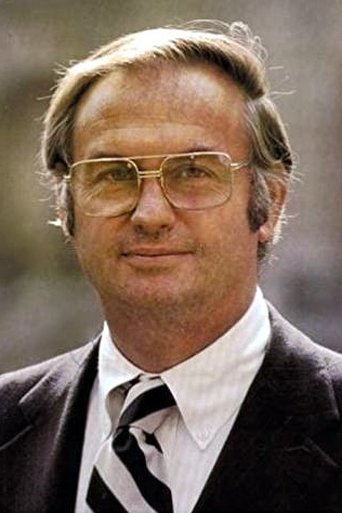

With the rise of political parties came the dawn of political compromise: nominees were selected because they were less offensive to some voters than those who might have been the best candidates (Franklin Pierce, James Garfield, Warren G. Harding, Gerald Ford). Two of the men profiled in this hour found the presidency beyond their abilities, while two proved themselves worthy of having been called to the highest office in the land.

Though the powers of the presidency have expanded with the growth of the nation, the process has been anything but smooth. These four presidents are benchmarks in the development of executive power (Andrew Jackson, Grover Cleveland, Theodore Roosevelt, Richard Nixon). Three stretched the office to its constitutional limits; the fourth overstepped those limits and brought on a new era of presidential weakness.

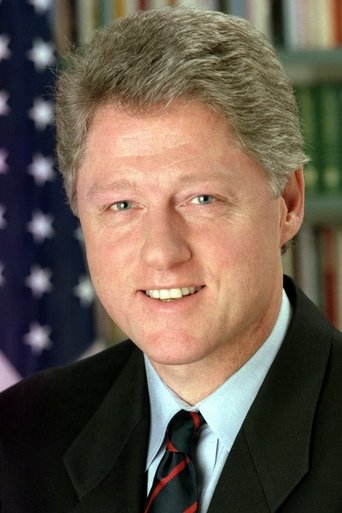

The final episode examines presidential leadership in an era of an increasingly divided government. The American presidency was conceived as one part of a larger system of institutions, and its effectiveness rests in part upon a good measure of cooperation among the branches. The presidents arrayed in this episode (James Madison, James Polk, William Howard Taft, Bill Clinton) suggest four different conceptions of governance within a constitutionally structured balancing act.